Beyond Reality: A Glimpse into The Past, Present & Future of Virtual Reality

If you’re like most people, you know someone who is currently caught up in the virtual reality craze. With all the new technology coming out, it can be hard to keep up with what’s new and what’s old news. Years ago, what most people thought of as virtual reality might have been Nintendo’s Wii. Although that console is somewhat outdated now, it was the closest thing to virtual reality that some have experienced. While you may not count as one of the 101.6 million people worldwide who owned a Nintendo Wii, you might have benefited from a friend who did. Although the Nintendo Wii console was groundbreaking at the time, it wasn’t the first disruption to cause a ripple in the gaming spectrum.

Let’s go back in time to see where it all began, shall we?

Mankind has always been intrigued by the way we view the world. “Long ago, our ancestors were trained to look at the walls and imagine a 3D world that is part of a story” (LaValle 2024 p. 24).

Ancient cave drawings of cave lion mates (note the lack of manes on the lions), found in Chauvet Cave, France.

LaValle wrote this in reference to ancient cave drawings. Ancient art depicts the ever-growing expression of stereopsis, which is the ability to perceive the world in three dimensions. It is only natural for humankind to evolve from the earliest conceptions of how we, as social beings, connect and share the world around us through images.

As for the earliest prototypes of VR, it is hard to define with the technology evolving quite rapidly falling in and out of relevance much like the rise and fall on an equalizer. In 1962, an American cinematographer and inventor Morten Heilig would make headlines for ‘The Sensorama’ as the first of its kind. A Machine made solely for the purpose of public entertainment. He described his invention as “The Cinema of the Future.”

The Sensorama focused primarily on stimulating the senses; it had wind effects and emanated the smell of a real New York-style pizzeria. Because it was a stationary machine, it had more of a peepshow feel, offering only a handful of visual options. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much of a market for such a big, bulky, and pricey machine, and eventually, it was lost to the history books. Morton Heilig would go on to create other inventions that never quite took off, with other companies developing flight training simulators and more research-oriented prototypes in their wake. (Morton Heilig, History of Information.com)

The idea of this type of entertainment medium went nameless until the 1980s, when officially the term “virtual reality” was coined to describe this area of increasing interest. But what exactly is virtual reality? LaValle defines it as “artificial sensory stimulation” (33) and describes it as the power of engineering one or more senses of an organism to become co-opted, at least partly, with their ordinary inputs replaced or enhanced by artificial stimulation. Interestingly, the term “virtual reality” dates to German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who had a different notion for it. Kant introduced the term to refer to the “reality” that exists in someone’s mind, as differentiated from the external physical world, which is also a form of reality. While these notions are centuries apart, they still resonate today.

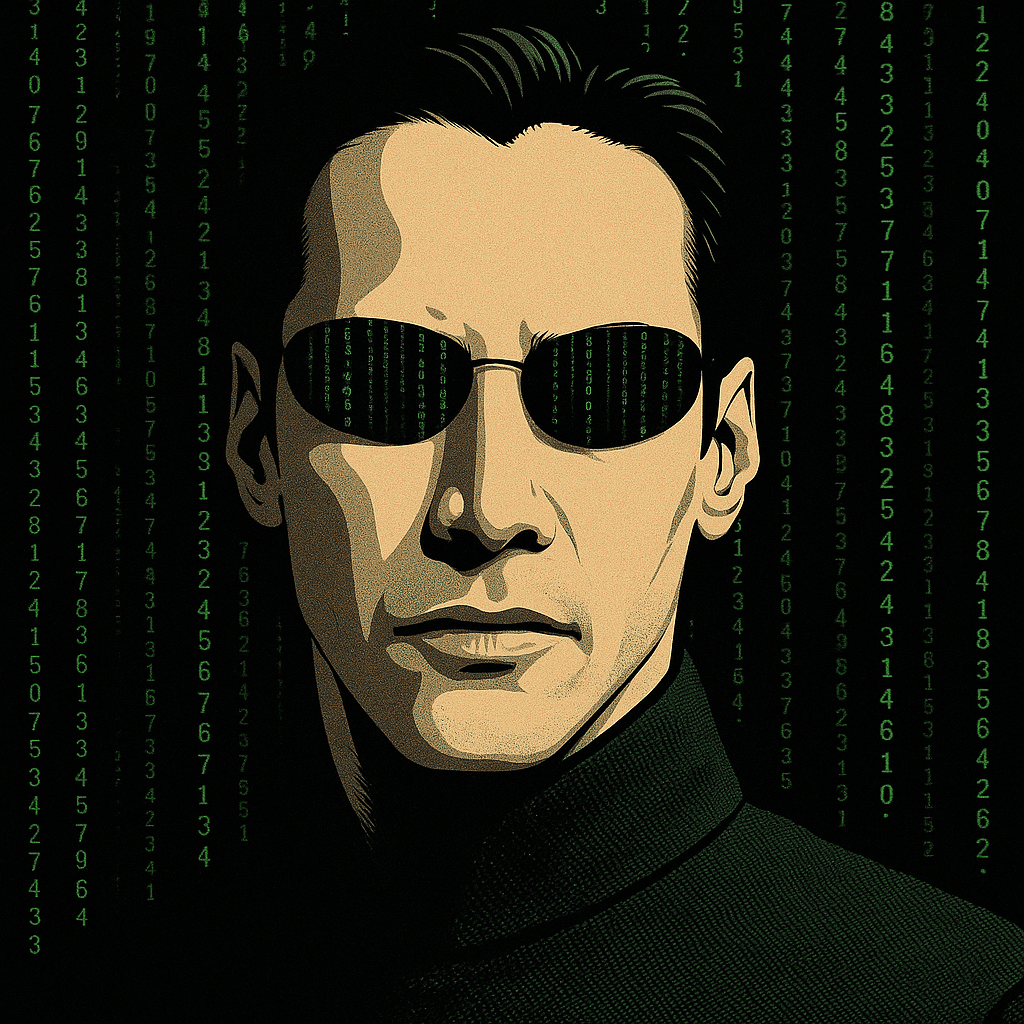

The 90’s seemed to open the doors for virtual reality in the gaming industry. It wasn’t until several failed attempts from some of the more notable gaming industry leaders, such as SEGA’s VR-1 and Nintendo’s Virtual Boy, that Sony PlayStation stepped in and seemed to capture the attention of market for a good run with the Sony Glasstron. Keep in mind that consumers of these devices represented a very niche market at the time, considering the cost. These were die-hard gamers, likely including those who flew first class. (“The Incredible Evolution of Virtual Reality.” Median.com) As we exited the 1990s, with The Wachowski Brothers’ film The Matrix hitting theaters, people were buzzing with the newly conceived idea of humanity possibly living in a virtually simulated world. However, virtual reality as we knew it fell into a black hole and went into virtual winter for about 15 years, largely due to over-hype, low fidelity, and overpriced hardware. (Rosenberg, Louis. ‘The Metaverse — of the 1990’s.’ Predict, 7 Jan. 2022)

Even through the dry spell, companies remained invested, and VR enthusiasts were still abuzz. It was only a matter of time before the 2000s became the decade that really stood out for virtual reality in the gaming market. (“The History of AR and VR: A Timeline of Notable Milestones.” HQSoftware) Hype began to increase again when in 2007 the Stanford CityBlock Project—a Google-sponsored research initiative at Stanford University—launched Google Street View, quickly followed by Google Street View 3D. It became clear that the tech world was changing rapidly, compelling companies to push the envelope in creating more attractive products that would appeal to consumers intrigued by this new technology. This shift was also slowly changing the way industries were evolving. The healthcare industry began to explore using VR for realistic surgical simulations to improve skills without the risk to patients. Additionally, VR was now being incorporated into educational classrooms, providing immersive learning experiences that enhanced engagement, fostered retention, and made education more accessible.

Movie releases like Spy Kids 3D and The Polar Express symbolized a moving cultural shift. While the third-person panoramic 3D experience appealed on screens, some audiences craved a more immersive first-person experience that only the gaming industry could deliver. Thanks to California entrepreneur Palmer Luckey, they wouldn’t need to wait much longer.

In 2012, Luckey launched Oculus VR to promote his Kickstarter campaign aimed at making his vision a reality. He showcased the Oculus Rift at major gaming conventions, attracting a significant following and catching the attention of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who would buy Oculus in 2014 for $2 billion. In the same year, Sony PlayStation introduced Project Morpheus, their newest VR headset for the PS3.

And the race was officially on again! After Oculus became Meta, three VR headsets have since been released, leading the market today. Morpheus eventually morphed into PSVR2 by 2023, which is still holding tight. HTC launched the Vive Pro 3 in 2016, a favorite among critics. And lastly Apple joined the ranks with the release of its expensive Vision Pro in 2024, to somewhat mixed reviews, while given that VR is still relatively in its infancy, a clear winner hasn’t yet been crowned. (Kim, Jonathan. “Apple Vision Pro: I like This Strategy.”)

While some might argue that consumers are the real winners in the evolution of virtual reality, others contend that technology is creating the illusion of unity while distancing us from genuine social interactions. However, with endless possibilities for generating communities through one-on-one and multiplayer experiences, social VR platforms may just be creating more meaningful connections where none existed before. (Marr, Bernard. “Future Predictions of How Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality Will Reshape Our Lives.” Forbes, 4 June 2021)

Whatever your take on it, it doesn’t look like it’s letting up anytime soon. The future of VR is expected to reach new heights, featuring super-lightweight, crisp, ultra-realistic graphics. One product currently on the market, the $13,000 TESLASUIT, may one day be replaced by a neural implant—a permanent chip that will mimic a full-body haptic suit, allowing you to taste, feel, and even hear the simulated world around you without the inconvenience of wires tying you down. (Full Body Haptic VR Suit for Motion Capture and Training.” TESLASUIT, 2023)

Some start-up companies you might want to invest in, that are already on the path to the future, include Ekto VR, which has created robotic boots that provide the sensation of walking, matching your movement within the game. The Ekto One robotic boot’s resemble futuristic roller skates—except, instead of wheels, they have rotating discs on the bottom that move to match the direction of the wearer’s movements. Another company, Mojo Vision, has been developing AR custom micro-lens optic contact lenses with micro-LED displays that project information inside the wearer’s eyes, allowing them to see whatever they choose. (“Mojo Vision, the Micro-LED Company.” Mojo Vision)

Imagine taking a vacation to one of those high-priced exotic locations you’ve only dreamed of visiting. While you’re there, you can shed any physical insecurities and step into the skin of your very own personalized avatar. Much like navigating Google Maps, you could walk or drive around, shop from store to store, and even buy merchandise from local retailers via their online websites, all while experiencing tourist attractions from the safety of your home—or better yet, through the new startup company you purchased this virtual vacation from, tailored to make the experience even more real. The entire island of Bora Bora could now be yours to explore simply by purchasing the game from home or buying a ticket through a local VR travel agency.

While these ideas may mortify those who fear it could lead to social alienation—where only the elite can afford the luxury of real travel with added safety and privacy, leaving the lower class with the only option of virtual travel—it is also seen as a glimmer of hope for those with disabilities and those who experience public anxiety to be able to experience things within their comfort zone.

Will society become so immersed in the future of AI and VR that the future of our realities become dangerously subjective?

One question remains: will it be the red pill or the blue pill? The choice is yours to make.

Story & Photos: Danyle D’Alene